This is the third and final entry in a collection of field commentaries.

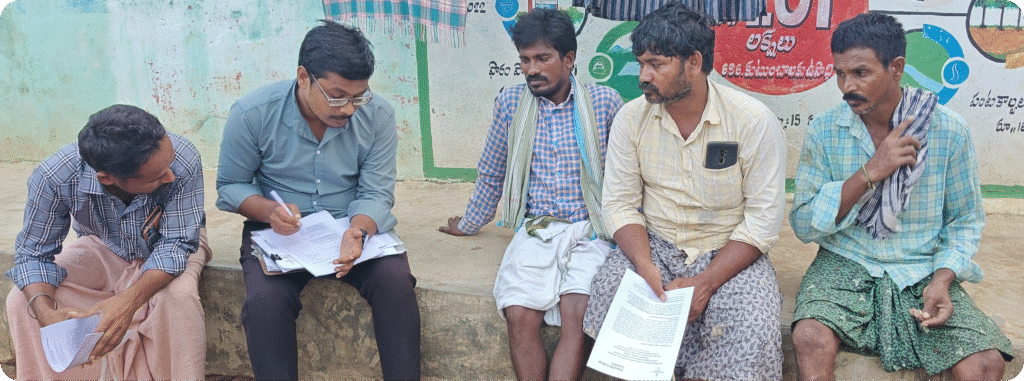

Recognizing the essential stakeholder groups within the Public Distribution System (PDS) of Srikakulam district, Andhra Pradesh, was a pivotal first step toward gaining a thorough understanding of the supply chain. This foundational effort opened the doors towards gathering critical primary data through direct engagement with diverse stakeholders across Srikakulam.

From the outset of engagement activities and the process of data collection, it was clear that the most valuable insights would come from farmers. Initially, it was assumed that the primary crop for the Srikakulam district was rice. Perhaps followed by green or black gram and sesame. These were assumptions borne out of our earlier research in a few regions of Andhra Pradesh. However, as we traveled to different parts of the Srikakulam district we discovered a much wider variety of agricultural practices that facilitated the cultivation of corn chillies, papaya, bananas, and more.

We observed two major crop cultivation patterns: rice in coastal areas, corn in non-coastal areas, and a mix of rice and corn in the buffer zones. In addition to these two major crops, some areas—such as G. Sigadam, a mandal (block) in the Srikakulam district—cultivate chilies as a primary crop. While the main oilseed crop is sesame (til) for edible oil, along with a newly introduced non-edible oil crop (Gidgidilu—*Crotalaria juncea*), palm oil, a perennial crop, is also seen in a few areas. Moreover, Ragi (finger millet), a superfood, is being cultivated though only in regions with access to irrigation facilities, such as rivers—Vamsadhara, Nagavali and Mahendratanaya—or canal-based water supply.

Despite the presence of these rivers, most of the irrigation in Srikakulam district relies on the monsoon, making paddy the most suitable crop. While ponds help provide irrigation water during the non-monsoon season, farmers acknowledge that it wasn’t anywhere near sufficient. Groundwater too was available only in limited quantities.

Image curated during data collection

Agriculture, the primary source of income for the vast majority of the local population, is highly dependent on irrigable water, whether it be rainwater during the monsoons or river/pond water. The prosperity of the villages and the communities within are largely dependent on the availability of irrigation water. Areas that have access to rivers like the Vamsadhara, Nagaveli, and Mahendratanya can grow more than one crop in a year and ensure robust crop rotation.

During our interactions, several villages raised concerns about the lack of irrigation water. The under-construction rain-fed barrage in Regulapadu is expected to help significantly in the near future. One farmer in a village suggested linking various ponds to store more rainwater. Some farmers are using solar pumps, but most agree that they do not perform as expected.

While the Vamsadhara River serves as a lifeline for several areas in Srikakulam, regions not receiving its water supply are pursuing various administrative channels to construct canals for irrigation to sustain agriculture.

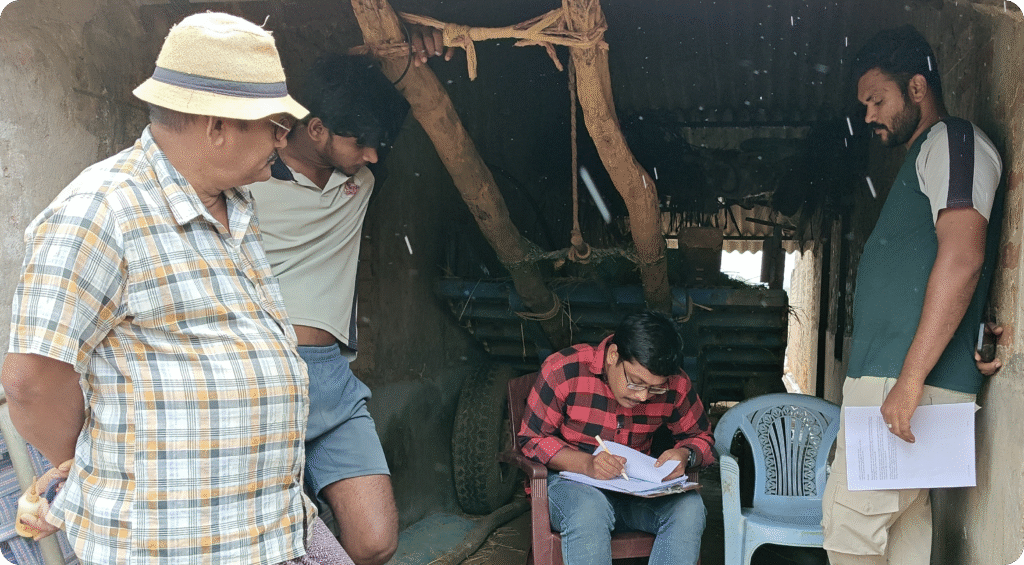

Image curated during interaction with a farmer engaged in conventional farming

Another valuable insight that came to light during the interactions was that farmers prefer using chemical fertilizers (urea, DAP, and potash) over organic farming, which remains limited in terms of green manures and bio-pesticides. Herbicides are commonly used to control weeds in paddy fields, while insecticides and broad-spectrum pesticides are applied in cases of pest attacks (bacteria, fungi, insects).

Some large-scale farmers are increasingly interested in using drones for pesticide spraying. Harvesting is done both manually and with harvesters, with labor shortages being a key driver for mechanized harvesting. Larger farm sizes and the need for quick harvesting with less physical labor are likely the main reasons for the increasing use of mechanized harvesting.

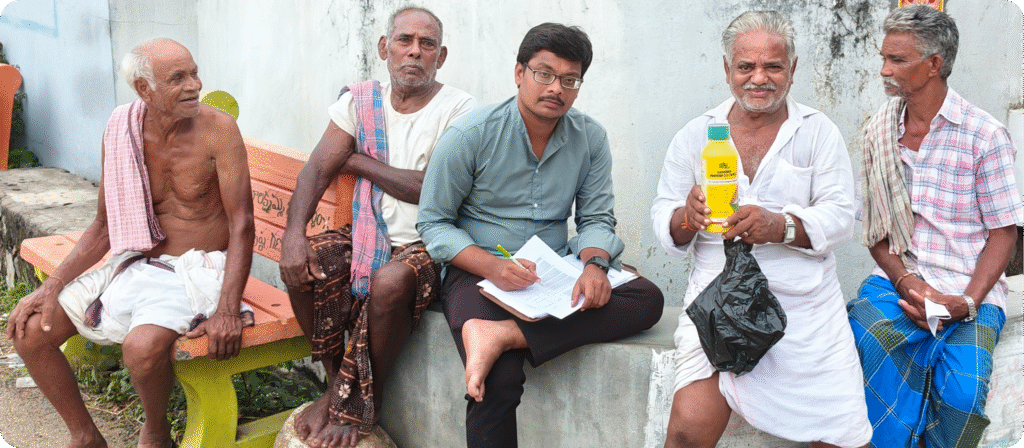

A group of farmers with the herbicide ‘Almix‘

Additionally, anecdotal evidence suggests that the younger generation is not very interested in pursuing agriculture to make a living, which is an emerging trend observed in many parts of India.

However, mechanized harvesting of crops like paddy and corn leaves stubble behind in the fields. Removing this stubble can be both physically demanding and costly for farmers. As a result, many opt to burn it, which takes little more than a matchstick to set it alight. Nevertheless, unlike the Delhi-NCR region, where the burning of crop residues contributes to severe air pollution during the winter months, many areas in South India have a longer gap between crop cycles—often lasting several months instead of just a few days—and higher temperatures. Factors that contribute towards the effective dispersion of air pollutants, thereby reducing the impact of stubble burning.

Our interactions with farmers offered invaluable insights into crop management, water challenges, and innovative farming techniques. Notably, some proposed the idea of linking village ponds to effectively conserve rainwater—a brilliant strategy to enhance agricultural productivity.

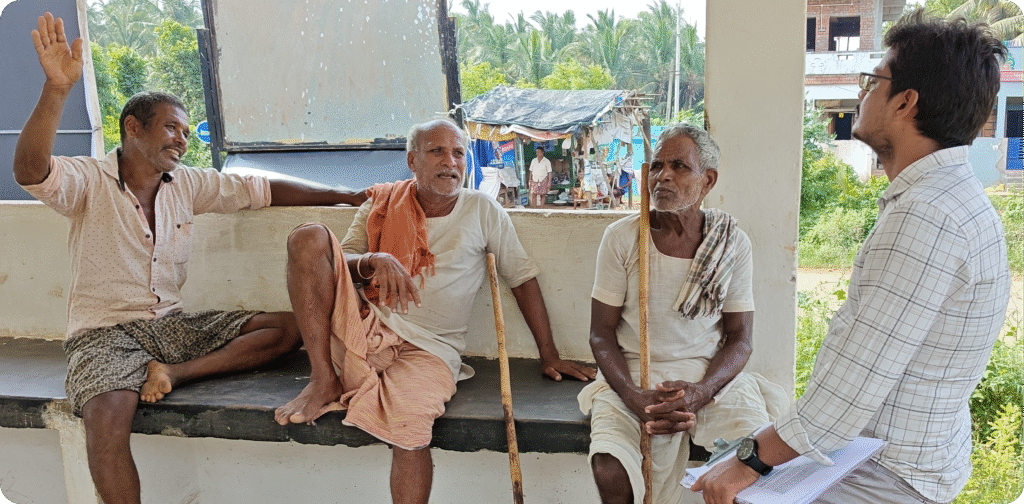

Image curated during interaction with farmers

By connecting with diverse stakeholders and tapping into their experiences, we gathered critical local knowledge that will shape the forthcoming phases of our study. This initiative not only fostered trust among the community but also illuminated significant challenges. Importantly, it showcased the power of community expertise to steer our research in a more impactful and sustainable direction for the future.

You can read the first and second entries in this collection of field commentaries here & here.

——————————————————

This blog was authored by Dr. Kanhaiya Lal.

About the author:

Dr. Kanhaiya Lal– Kanhaiya is a consultant at the George Institute for Global Health and a pivotal Project Scientist for the NIHR Global Health Research Centre for Non-Communicable Diseases and Environmental Change. With an impressive track record of over 12 years in environmental science and engineering—seven of which have been dedicated to research and projects following his PhD—Dr. Lal is a leading expert in conducting comprehensive environmental assessments of water, soil, food, and air quality. His impactful work also addresses critical issues such as climate change, health, waste management, and environmental compliance. A prolific contributor to environment and health research, Dr. Lal has authored ten peer-reviewed articles and reviews which have been published in over 25 international journals, making a notable impact in the field and advancing public health through environmental initiatives. Explore his publications is full here…

This research was funded by the NIHR (Global Health Research Centre for Non-communicable Diseases and Environmental Change) using UK international development funding from the UK Government to support global health research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the UK government.