24 January 2025

With heavy monsoon showers that transformed roads into rivers, we set out in early September in 2024 to meet communities in the Sarguja district of Chhattisgarh located in central India. It is in this district that we are trying to understand how public food procurement programs (PFPPs) can improve dietary diversity, and food and nutrition security, and reduce diet-related non-communicable disease risks, all while achieving environmental benefits.

To understand the context of local food practices, food sourcing and the local environment, we engaged with different stakeholders. At the NIHR Global Health Research Centre for Non-Communicable Diseases and Environmental Change, liaising with community is an integral part of our work as it helps co-create solutions based on community perspectives, experiences, and insights.

Our field team, some of whom are members from the local community, have been conducting extensive work to understand the current practices in food sourcing and building and sustaining long-term relationships with community members and the local stakeholders. They have collaborated with grassroots organisations such as Bihan, Sangwari, PRADAN, and Chaupal, which have been working with tribal communities for many years and focus on the holistic development of these communities. This participatory approach fosters ownership and understanding among communities, provides a platform for advocacy, and increases the likelihood of our research leading toward sustainable change.

Local changes, local challenges

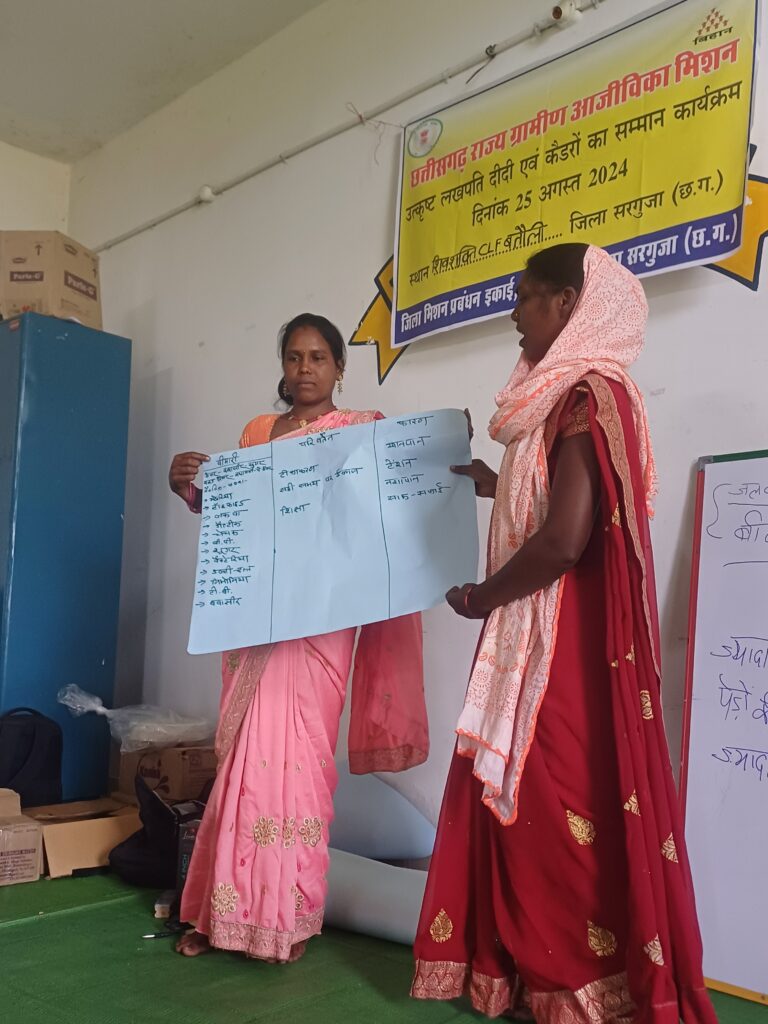

Our first stop was the Batauli cluster office, where a group of 36 women from the Batauli block (the district subdivision) had gathered for the day. These women are members of different Self Help Groups (SHGs) that educate the community on a range of subjects such as food, nutrition, health, water, sanitation, hygiene, waste management among others.

Chhattisgarh’s State Rural Livelihood Mission (SRLM), Bihan, mobilises 85-95 per cent of the women from each household in the district into these SHGs. Additionally, Bihan has also developed a multi-tier structure of women collectives like Village Organisations (VOs) and Cluster Level Federations (CLFs) that facilitate access to formal credit, support for diversification and strengthening of livelihoods and access to entitlements and public services.

Our interactions with the SHG members highlighted their awareness of local challenges and their valuable insights into potential best-case scenarios and opportunities for intervention.

We started our session with an icebreaker activity following which we discussed the linkages between environmental change and health outcomes with the help of a short video. We asked the group to reflect on how the environment has changed over the years, its impact on health and well-being, such as changing patterns in illness, with particular emphasis on change in eating habits.

As the discussion unfolded, women noted changes in climate patterns, including erratic and extreme weather events, extensive use of chemical fertilizers, increased household waste, industrial pollutants, and loud music during events and celebrations as practices adopted over the last 15-20 years, reducing their quality of life. The women also noted positive changes, such as the shift in drinking water sources from rivers to tube wells or hand pumps, the availability and accessibility of education, and vaccination and treatment facilities.

Next, we discussed changes in eating habits. We learnt that rice has almost entirely replaced the cultivation and consumption of other grains such as millet and barley (mota anaj). Additionally, women noted how easy availability and therefore, the increased consumption of packaged and fast food among the younger generation could be contributing to diseases like diabetes and hypertension.

They were also cognisant about the waste from food packaging increasing plastic pollution both at the community and household levels.

Some members also discussed how ways in which communities convene and celebrate events has also changed over the years. Disposable plates and bowls are more commonly used in community feasts than plates that were traditionally made from leaves adding to plastic waste.

In the past, most household waste was biodegradable and served as a primary source of organic fertiliser for crops, so waste management was not a significant concern. However, the rise in single-use plastics, disposables, and packaging materials, without an adequate waste collection system at the village level, has made waste management a major challenge.

Champion change-makers

Our team had been engaging with women from SHGs through various formal and informal consultations including focus group discussions. Due to their strong roots to the community, networks and understanding of the local context and challenges, these women are key stakeholders for us. Their comprehensive knowledge of the community’s history and needs, combined with their proactive leadership, is crucial in developing sustainable and impactful solutions.

“I want my village to be clean and healthy, and through education, people can be made aware of these important things like cleanliness, pollution, nutrition and its impact on our health.” (Sanitation worker, Swachch Bharat Mission)

“Women often are not able to understand the social structures and norms of discrimination, which they often feel targets of. I would want to change these societal norms in my village, and work towards eliminating caste-based discrimination and untouchability. Alcoholism is another issue my community is struggling with, which I am currently working on.” (Gender Master Trainer)

“When teenage girls are married early and get pregnant, it significantly impacts their health, hence through my work, I advocate to stop early girl child marriage in my community so that new mothers are healthy along with their newborns when they get married after the age of 18.” (Food, Nutrition, Health, WASH- Water, Sanitation and Hygiene)

Community-run Kitchen Gardens

The next morning, we visited villages home to ‘Pahadi Korba’ tribal communities. These communities have been identified by the Government of India as particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups, or PVTGs 1 , due to limited access to resources and infrastructure, including barriers to health, education and livelihoods. Their location on steep, hilly terrain makes irrigation challenging, leaving them dependent on rain-fed agriculture, which is affected by change in rain patterns.

The solution comes in the form of kitchen gardens— using backyards for growing vegetables, herbs and fruits.

Traditionally kitchen gardens have been a practice in these communities but slowly it started losing its importance because of improved road connectivity, expansion of markets, among others socio-economic factors. While these markets exist, people only buy what they can afford, and the nutritional aspect is often neglected.

Kitchen gardens may be a potential intervention based on our formative research and community engagement. One of our partner organisations, ‘Chaupal’ is implementing this solution with 700-800 families to see if it has potential to upscale.

Traditionally kitchen gardens have been a practice in these communities but slowly it started losing its importance because of improved road connectivity, expansion of markets, among others socio-economic factors. While these markets exist, people only buy what they can afford, and the nutritional aspect is often neglected.

Kitchen gardens may be a potential intervention based on our formative research and community engagement. One of our partner organisations, ‘Chaupal’ is implementing this solution with 700-800 families to see if it has potential to upscale.

With support from the state government and civil society organizations in the form of seeds and fencing to keep out predatory animals, and by routing the water now available from pumps installed in the villages to drain via the gardens, the communities are successfully growing a wide variety of produce in these kitchen gardens. Among the crops, we saw flourishing were sweetcorn, tomatoes, different types of gourds, lentils, beans, turmeric and Indian jujube.

Kitchen gardens, a sustainable, community-led solution and have become a key source of nutrition. They also provide an opportunity to strengthen the sense of community, as families help each other out by sharing their produce, and selling surplus crops to bring in additional income.

We concluded our visit with an authentic and fulfilling Chhattisgarhi lunch at the kitchen-cum-restaurant ‘Gadh Kalewa’ in Ambikapur. This establishment, owned and operated by trained women from a SHGs. The menu comprised of nutritious indigenous dishes millet snacks, local grown pulse, french beans and chilli tomato chutney not only promote healthy food habits, but also reflect the restaurant’s commitment to responsibly sourcing indigenous ingredients from local farmers.

We concluded our visit with an authentic and fulfilling Chhattisgarhi lunch at the kitchen-cum-restaurant ‘Gadh Kalewa’ in Ambikapur. This establishment, owned and operated by trained women from a SHGs. The menu comprised nutritious indigenous dishes millet snacks, local grown pulse, french beans and chilli tomato chutney not only promote healthy food habits, but also reflect the restaurant’s commitment to responsibly sourcing indigenous ingredients from local farmers.

Community members — such as the ones we interacted with — play a key role in informing the co-creation and implementation of interventions on health, food, and environment. The visit has also provided us with an understanding of food procurement programmes, the health needs, existing policies and the changes necessary. By collaborating with community partners, we aim to ensure our interventions are relevant, effective, and sustainable.

——————————————————

This blog was authored by Chhavi Bhandari, Maroof Khan, Deepika Saluja, Deeksha Bhardwaj, Sangeeta Sharma, Sudhakar Reddy Bulla, Emma Feeny

About the co-authors:

Chhavi Bhandari- Chhavi Bhandari leads the George Institute of Global Health’s the Impact & Engagement program of work in India, which includes policy engagement, and community engagement. With her multidisciplinary experience in the healthcare industry, Chhavi works with national and state governments, hospitals, non-governmental organizations, universities, pharmaceuticals, medical technology, multilateral organizations, and insurance firms worldwide to increase the impact of the institute’s health and medical research.

Maroof Khan- Maroof is the Community Engagement and Involvement (CEI) Manager for the NIHR Global Health Research Centre for Non-Communicable Diseases and Environmental Change. He oversees the planning and execution of CEI initiatives in India and supports CEI coordination in Bangladesh, India, and Indonesia. Maroof works closely with researchers, policy makers, and civil society organisations to bring community voices to the forefront in public health research.

Sangeeta Sharma- Sangeeta Sharma is a Research Officer at NIHR Global Health Research Centre for Non-Communicable Diseases and Environmental Change. With more than a decade’s experience in the public health field, Sangeeta has contributed to numerous projects. Implementing programs pertaining to mother and child health, infectious and non-communicable illnesses, community health worker capacity building, monitoring, and evaluation.

This research was funded by the NIHR (Global Health Research Centre for Non-communicable Diseases and Environmental Change) using UK international development funding from the UK Government to support global health research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the UK government.

[1] The Central Government of India has recognized 75 tribal communities as Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs) based on the recommendations of the Dhebar Commission (1960- 61) and other studies conducted during the Fourth Five-Year Plan. These communities were placed in a special category due to their significant development disparities compared to other tribal groups. They were initially referred to as Primitive Tribal Groups, which later came to be identified as ‘Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups’ (PVTGs).

The identification of such groups was based on one or more of the following characteristics:

- Preservation of pre-agricultural practices,

- Hunting and gathering practices,

- Decreasing or stagnant population growth, and

- Relatively low levels of literacy in contrast to other tribal groups.

In the present context, Chhattisgarh has identified and listed seven such groups under the PVTG category including Pahadi Korba tribe.