This blog shares reflections from field visits in Andhra Pradesh by the SMARThealth team and aims to capture the experience of conducting research in extreme heat, the profound wisdom communities who endure such extreme heat daily offer, and how these experiences shape climate-health research towards inclusivity and resilience.

Fieldwork during the summer months in Andhra Pradesh is a real adventure that lingers in one’s memory forever. The Sun seems to be right above, the wind is still, and the temperature is so high that even the shaded places under the trees provide no relief by midday. The increasing heat is a trial of stamina, an attrition of endurance, and a test of one’s empathy and adaptability.

Our Primary Health Care (PHC) research team, as part of the Heat-Health research under the NIHR Global Health Research Centre for Non-Communicable Diseases and Environmental Change, visited various villages in Srikakulam and Parvathipuram Manyam districts during our formative phase activities. Our goal was to understand how heat affects communities and what coping measures are in place. Each field visit brought new insights, not just into heat-health science but also into people’s resilience and ingenuity.

In the Field: Learning from Everyday Resilience

During a visit to Srikakulam, I accompanied an Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) worker on her household rounds. She carried a notebook, a steel water bottle, and oral rehydration salts. When I asked how she managed the heat, she smiled and said,

“We cannot stop our work; people depend on us. We do start early, take quick breaks and remind others to do the same.”

A simple answer. But one that captured what many a field visit has taught us. Communities already possess practical adaptation systems. They may not label them as heat resilience strategies, but they are deeply insightful. People adjust work timings, share water, and look out for neighbours. Actions born from lived experiences rather than instructions.

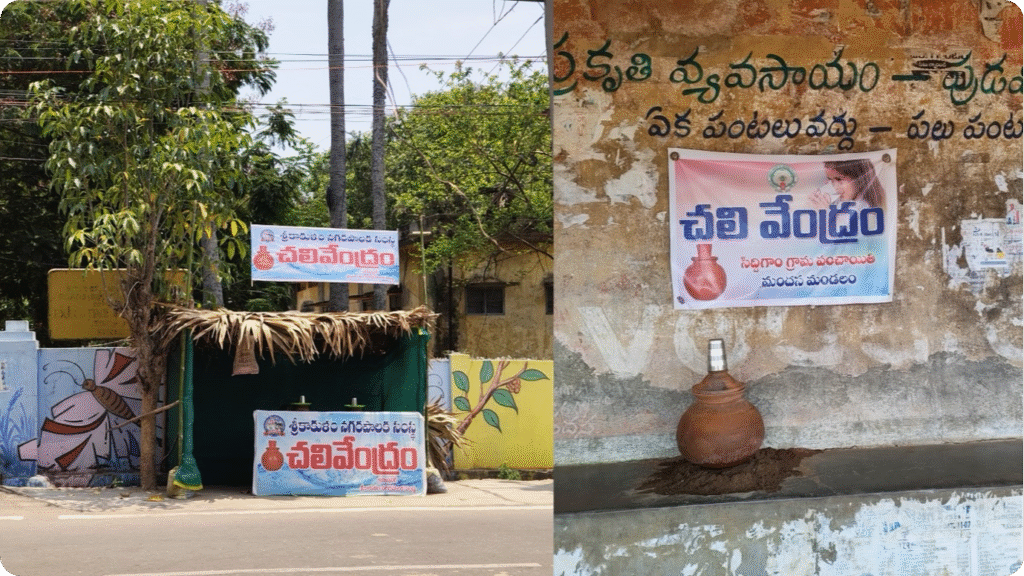

Across all these villages, similar ideologies and practices emerged in everyday acts like storing water in clay pots to keep it cool, cooking early in the morning, or resting under trees before resuming fieldwork. These are not just coping mechanisms but expressions of community-based climate adaptation that have been built silently over generations.

Cooling Points

Research in the Heat: Small Adjustments, Sizeable Lessons

It took a certain type of resilience to conduct fieldwork in these conditions. Interview planning required early start times and monitoring of temperature forecasts. We carried drinking water, worked in shaded places whenever possible, and paused interviews when the heat became overwhelming.

The experience underscored for us the acknowledgement that ethical research is not just about consent forms and protocols, but also about care and making these small changes to ensure that the considerate and respectful side of the research community is intact.

When participants believe that their comfort and safety matter, they share more openly, thus making the research richer and more authentic.

Heat and Inequality: Whose Burden is Heavier?

It was during our interactions with the community members that we realised that heat still does not have the same impact on everybody. The most affected were outdoor labourers, older adults and expectant mothers. Women described how cooking and fetching water in the sun had become more strenuous, with metal containers too hot to touch. Revealing how global warming and climate change has deepened the divide and worsened prevalent social and gender disparities.

Even though exposure to sun and heat might not appear to be noticeable, it has a larger impact on the people who work under its burning gaze. The acknowledgement of these disparities gives researchers and decision-makers the opportunity to come up with solutions that can help shield the underserved and least protected.

Strength in Community

Despite all the challenges, what stood out most was the resilience of communities, and it was not the dramatic kind. It was the quiet, everyday strength of people helping each other through the heat. Health workers continued with their household visits, families checked on elderly neighbours, and local leaders spread messages about keeping themselves hydrated and avoiding peak sun hours.

Their motivation was contagious. It reminded our team that research is not a one-way exchange. The communities we visit are not just participants; they are partners and teachers. Their lived experiences are the foundation of effective climate-health solutions.

Image curated during a stakeholder workshop

Reflections: Adapting Together

Working through heat entails putting science and humanity back into a different light. There, patience, respect, and humility are understood better. Each visit serves as a reminder to us that resilience is not only about surviving; it is also about caring, learning, and adapting together.

As the project continues, these lessons will shape how we plan, communicate, and collaborate within ourselves and the community. We must design fieldwork that respects local rhythms, co-create messages that reflect people’s voices and test interventions that align with the priorities of the communities.

Every field visit confirms a simple truth. The strongest solutions often begin in the very places where people are already finding ways to cope. The best research listens to them first and then, with the help of those who live the story daily, determines how to act.

——————————————————

This blog was authored by Akhil Gurram.

About the author:

Akhil Gurram– Akhil is a Research Officer at The George Institute for Global Health, India, working primarily with the Primary Health Care team at the NIHR Global Health Research Centre. His work focuses on the investigation of the social determinants of health and emphasises improving care for non-communicable diseases. Deeply interested in the use of technology and community-based approaches to make healthcare more accessible and effective, Akhil is committed towards ensuring equitable public health research.

This research was funded by the NIHR (Global Health Research Centre for Non-communicable Diseases and Environmental Change) using UK international development funding from the UK Government to support global health research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the UK government.